Peter Henry Emerson

Peter Henry Emerson

You can read up on the Victorian photographer Peter Henry Emerson on almost a dozen excellent sites...and you'll learn the same basic facts from each of them. I know this because I tried it. What many fail to explain is how his fundamental questions about what photography actually was would influence an on-going international debate by (admittedly very introspective) photographers well into the 1970s if not beyond (trust me, I was there). Is photography art? Or is it just a mechanical process to record a moment in time?

You may well laugh at the naivety of this question; of course it can be both. But please join me as I reveal some of the attitudes prevalent in Victorian times that shaped both Emerson's questions and his answers.

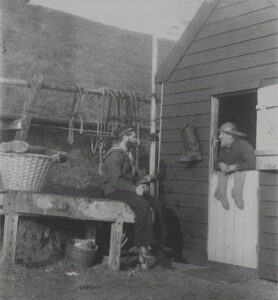

Coming Home from the Marshes

Emerson was born in 1856 on a sugar plantation in Cuba, owned by his American father, who died when Peter was was but a child. When Peter turned thirteen, he and his British mother relocated to England, where in 1885 he gained a medical degree from Clare College, Cambridge. His career as a surgeon was short-lived however; he'd purchased his first camera some three years earlier and, on graduating from Cambridge, he helped found the Camera Club of London. By 1886, he'd been elected to the Council of The Photographic Society (which would eventually become The Royal Photographic Society), and had given up medicine to pursue a career as a writer and photographer. 1886 also saw the publication of his first album of photos entitled Life and Landscape on the Norfolk Broads, thus beginning a nine-year love affair with the East Anglian countryside.

Gathering Water-Lilies

I find it impossible to look at Emerson's work and not see great art. There's a possibly apocryphal story (it may actually be true) of a French painter, Paul Delaroche, who some fifty years earlier had proclaimed, "From today, painting is dead!" on seeing a daguerreotype for the first time. And yet, even with great technical advances over the ensuing years, photography only made some genres of painting redundant (and even then only vaguely so): the recording of battles or the documenting of archaeological finds, for instance.

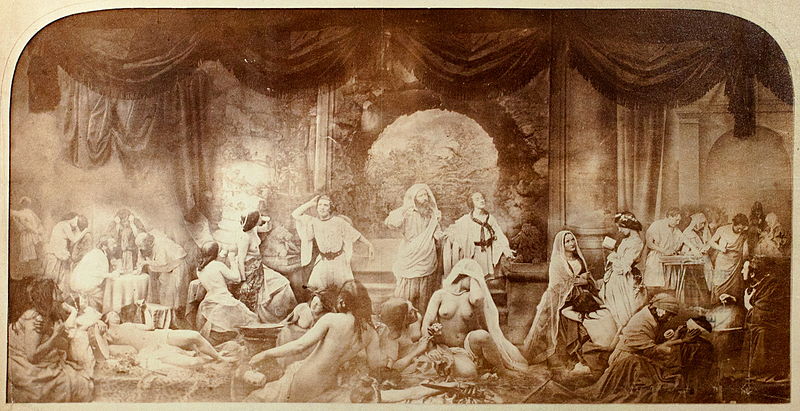

At the inaugural meeting of The Photographic Society in 1853 (thirty-three years before Emerson was co-opted to its Council), miniaturist painter Sir William Newton delivered his paper "Upon Photography in an Artistic View". Members heard how photographs might be useful so long as they were taken "in accordance with the acknowledged principles of Fine Art", i.e., emulated paintings, especially those in the historical and portraiture genres.

Challenge accepted, four years later Oscar Rejlander produced The Two Ways of Life (The Sacred and the Profane) from thirty separate negatives, and the Victorian equivalent of photoshop - the combination print - had arrived. Hailed as a masterpiece in its time, it may perhaps be regarded as art that still has some worth today - just not in the way the artist ever intended.

Oscar Rejlander: The Two Ways of Life (1857)

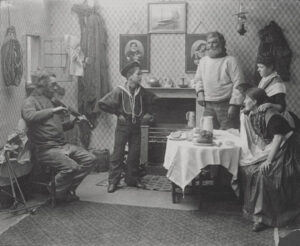

H. P. Robinson: When the Day's Work is Done (1877)

Twenty years on, Henry Peach Robinson had finally beaten the art of combination printing into submission (frankly I'd have made those wooden receptacles in the bottom right-hand corner slightly darker, all the better to frame the couple in the middle).

Though the results are undoubtedly painterly in a sense, to modern eyes they look at best overly idealistic and sentimental, almost chocolate-boxy. And with good reason, since they reflect the state in which British academic painting had become stuck, exactly the sort of art that Richard Cadbury started to feature on Cadbury's chocolate boxes towards the end of the 19th century.

Contemporaries of Robinson, such as John Thomson, were by this point celebrated photographers in their own right (Thomson was a favourite of Queen Victoria with good reason), and they could make a decent living by selling themed albums of their work to the public - but they were never considered artists as they would be today. It's into this claustrophobic, academic world that P. H. Emerson stepped.

Ricking the Reed

From the beginning, Emerson had some very set ideas about the images he wanted to produce. It's often said that he was influenced by naturalistic French painting (often painted en plein air - out of doors - and more and more commonly featuring ordinary workers instead of classical gods for their heroic subject matter), and the photos that made up Life and Landscape on the Norfolk Broads reflect this perfectly. Ricking the Reed is a painterly image in the very best sense of the word - the skilled composition demands a broad canvas, which Emerson gives it. More importantly there's no reliance on multiple negatives nor on retouching. But is it posed? Quite possibly, but not in the way H.P. Robinson's were posed. Exposure times were the shortest they'd been by this point, but given the depth of field (how sharp or blurry things appear - in this case mostly sharp), they were still going to be a quarter- or a half-second in length, necessitating some amount of posing.

Though Life and Landscape on the Norfolk Broads brought about little change to the accepted precepts about photography as an art form, at least Emerson had a foothold in an institution where his ideas could initiate some debate.

At Plough, The End of the Furrow

Unwilling to rest on his laurels, and unconvinced that having everything in sharp focus best replicated how we as humans see the world, Emerson began to experiment with differential focusing for his next album of prints, Pictures From Life in Field And Fen (1887). If you enlarge the above photo At Plough, The End of the Furrow from that volume, you will see how the ploughman is now out of focus, leaving the horses in sharp relief. This second album was closely followed by a further two offerings, Idylls of the Norfolk Broads and Pictures of East Anglian Life, in 1888.

In 1889 he published a treatise detailing his vision for photography, Naturalistic Photography for Students of the Art. It was described by one writer as "the bombshell dropped at the tea party", claiming as it did that realistic photography would undoubtedly replace the contrived photography of the day. The gauntlet had been dropped; the debate had well and truly begun, and Emerson had set himself up against the weight of the British academic establishment.

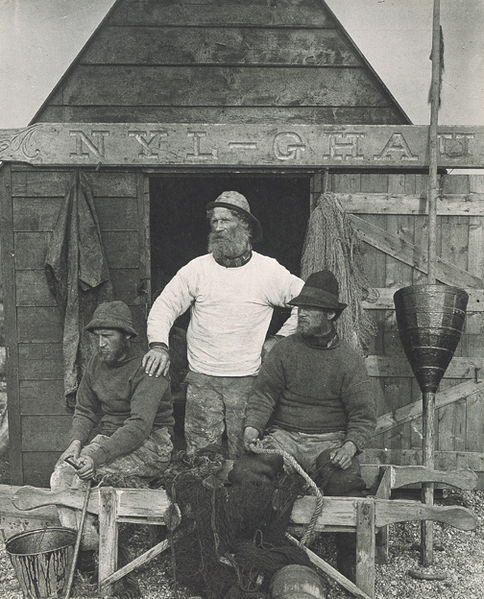

East Coast Fishermen

Though Emerson eventually came to recant his beliefs and principles, the questions he'd raised about photography's role struck a chord with the next generation of photographers, the influential Alfred Stieglitz (considered by some to be the father of modern photography) among them. The very last album of photographs P. H. Emerson published came in 1895 (a mere nine years after his first): Marsh Leaves.

When I came to write Big Bona Ogles, Boy: The Case of the Mendacious Medium, it was crucial that the cook, who had important information (even though she didn't recognize its significance), could not be contacted easily. When I decided to retire her to the seaside town of Orford on the East Anglian coast (because it has a castle where the climax could be played out), I realized there were photos of Emerson's that could provide me with a mine of information about her living conditions there. The perfect source material!

Here are some of his lesser known shots that I studied in detail whilst researching that particular book. I found the perfect cook amongst his images. I also found her perfect cottage. Note how the walls act as storage and how the very limited space needs to function for multiple purposes. Victorian IKEA! Enjoy!