A Girl for £5

The Scandal That Determined Our Age of Consent

‘I read in the paper just the other day that a girl was sold off by her parents for the grand sum of five pounds. Sold off! For five pounds! Can you imagine it? Probably shipped out of the country to work as a slave, as likely as not. Disgraceful! Do you think you’re worth five pounds to me, Lizzie?’

‘No, ma’am, of course not!’ It was a ridiculous amount of money.

‘Oh, I expect you are,’ she said thoughtfully, ‘but then I’m not after your soul, girl, only your services.’

The reference that old Mrs Ledden makes in the second chapter of The Bridge of Dead Things reflects one of the darker scandals to hit London in 1885. On Monday July 6th, the Pall Mall Gazette (yes, the newspaper which claims that Lizzie Blaylock hails from Walthamstow) published the first of four instalments of The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon, a series of articles with sensationalist headings such as “The Violation of Virgins”, “The Confessions of a Brothel-Keeper”, “How Girls Were Bought and Ruined”, and most notably “A Child of Thirteen Bought for £5”, which told the story of “Lily”, a thirteen-year-old virgin who was sold into prostitution by her alcoholic mother.

The Maiden Tribute was the brainchild of the Gazette’s editor William Thomas Stead, who together with colleagues from the Social Purity movement and the Salvation Army wanted the government to pass a bill raising the age of consent from 13, as it was then, to 16, as it is now. His aim was to stir up a public outcry that would force the reluctant government into doing this quickly. But the articles were so lurid that W. H. Smith & Sons, who had a monopoly on news stalls, refused to distribute it, so volunteers from the Salvation Army took to the streets to sell it instead. According to Wikipedia: “Such was the demand for the paper that crowds gathered in front of the Pall Mall Gazette offices fighting tooth and nail for a copy. Second-hand copies of the paper sold for as much as a shilling—twelve times its normal price.”

The public’s response was all that Stead could have wished for: protest meetings were organized, thousands marched on Hyde Park, and within four weeks the bill was passed, but not before rival newspapers started unearthing the true facts about “Lily”. It turned out that “Lily” was in fact a girl called Eliza Armstrong and the reason Stead knew all about her was because he and his colleagues had engineered the whole scandal to suit their exact needs. Stead was the “gentleman” who had purchased Eliza Armstrong through a reformed procuress (with the sole intention of proving that it could be done) and she was now living safely with their Salvation Army friends in France. She was reunited with her parents, who claimed that they thought she had been sold into domestic service, on August 24th.

Ordinary people and politicians alike were justifiably furious at having been manipulated in such a manner. Stead and his co-conspirators were brought to trial, and on the 10th November he and two others were found guilty of abduction and procurement. Stead received three months imprisonment and by all accounts was a model prisoner.

![mwts-rms-titanic-400x251 The Titanic leaving Belfast. Photo by Robert John Welch (1859-1936), official photographer for Harland & Wolff, April 2nd 1912 [PD]](http://michaelgallagherwrites.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/mwts-rms-titanic-400x251-1.jpg)

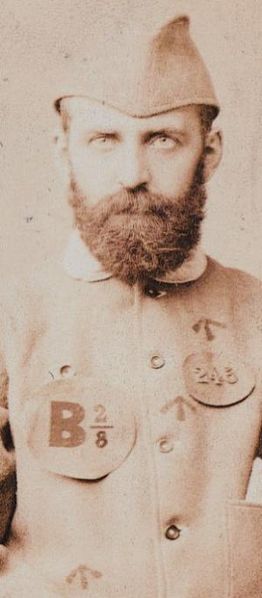

There are two further facts which I find fascinating. Firstly, on his release Stead asked the prison governor if he could keep his prison uniform, and every November 10th he would dress up in it to celebrate his great “victory”. The photograph you see at the top of the article may well be an image of this and not a document of his time in prison. Secondly, Stead often joked that he would die at the hands of a lynch-mob or by drowning. In 1892, just as he was developing an abiding though thoroughly commercial interest in spiritualism [Editorial comment: the following year he began publishing his spiritualist journal, Borderland, which ran for five years; in 1909 he set up an agency where the public could contact their loved ones through an assembled group of resident mediums], he published a story entitled From the Old World to the New, in which the survivors from a ship that had collided with an iceberg are picked up mid-Atlantic by a conveniently passing vessel. Some people interpret this as Stead foretelling his own death. They may well be right. On the 15th of April 1912, William Thomas Stead met his end on the ill-fated Titanic’s maiden voyage. After helping the women and children into the lifeboats, he surrendered his life jacket to one of his fellow passengers. His body was never recovered.