FABULOUS FRIENDS

BERIC LIVINGSTONE

Meet Beric Livingstone. I first met Beric through a mutual friend, actress Nicola Faraday, who played Snowball in TV's Bad Girls.

He read an early draft of The Scarab Heart before it was published and was taken with the poem Merit writes about death and love. More recently he's read Gooseberry and Octopus, and we are currently in talks about him producing and narrating an audiobook of Octopus: The Case of the Throttled Tragedienne.

Here's a bigtime salutary note for me from the past: a 9- or 10-year-old Beric and his mum may well have jostled past me at one of the tables outside Maison Bertaux. I occasionally went there with my boyfriend at the time, Ron Meerbeek, as we planned our band Two Big Boys together.

If there are any authors out there who are considering turning their novels into audiobooks, I can thoroughly recommend Beric. You can contact him on his website.

Beric writes:

"A croissant and a chocolate éclair please," and I can already taste them - the best in London - as Michele ties the box with a purple ribbon that she spirals into a can-can flourish.

I'm six, and mum and I have walked from our house round to Maison Bertaux - an occasional treat and an olfactory odyssey. Through the wholemeal haze from the bakery; past the municipal baths (soggy cocktail of complacency and chlorine); on through the detergent effervescence of the laundry; the sweets and paper from the newsagent; the wholesome homity pie steam of Cranks restaurant; clay dust from the Craftsmen Potters Shop; round the corner and on towards Berwick Street Market: flowers and fruit; an old cauliflower on the kerbside; cardboard boxes conceding flaccid surrender in the remains of yesterday's rain. Past the Revue Bar, through a vapour of urine and tarmac and beer and sweat. Then an arid wallop of roasting coffee and we're nearly there, my little legs gamely keeping up, my hand in mum's.

Inside, it is short pastry and cream and glazed strawberries and chocolate and custard and quiche and cooked tomatoes and café au lait. It is mess and bustle and indulgence and joie de vivre; independence and Franglais and defiance and romance. It is the delicacy and mania of sugar; the sensuality and bonhomie of butter.

And, in turn, through its doors comes Soho. And I won't waste time with a mawkish paean to that lot - us lot; not yet - I'm only six, and there's enough syrup in the contents of the window.

As the lucky will know, the patisserie is still there - and so is Michele. Monsieur Bertaux had been a former member of the Paris Commune who, after its brief, bloody incandescence, fled to England and established his little shop in Greek Street in 1871; Michele started as a Saturday worker there and has been running the place for as long as I can remember.

We will be open for a short time this weekend (Sat/Sun) from 9am - 4pm! Please call ahead to place your orders. Takeaway only. pic.twitter.com/3UuqEuy85O

— Maison Bertaux (@Maison_Bertaux) June 12, 2020

You can usually find her hard at work conducting the epicurean orchestra, and her actress sister Tanya (blonde to Michele's dark) overseeing the adjoining art gallery; both shimmering charisma and as much a part of the magical glue keeping the whole fairyland together as the crème pâtissière in the tartes aux framboises. There's an old upright piano; there's 'Liberté! Égalité Fraternité!' drawn on mirrors; there are little tables packed so buttock-rubbingly close together that acquaintanceships are ipso facto created, and conversations sparked.

Each time I go there, these days, I feel a bit of panic along with the joy. Because if that place goes, a little of my boyhood soul will go too. If you think I'm exaggerating, you may not have tried their pastries.

More than forty years since I first stepped through the doors; more than 150 since they opened. That's good going by most standards; extraordinary, surely, for Soho. Because in cities more than in villages - and in flagrantly capitalist capital cities most of all - you are forced right up against the window of things changing. Your nose is squooshed against the glass and you either have to watch what you knew morphing and vanishing before you, or keep your eyes very tightly shut indeed.

I remember a shop on one nearby corner that seemed to change hands every few weeks: it was the storefront for Pam Hogg's amazing jumpsuits; it was a jewellery designer; it was Junior Gaultier; it was a sandwich bar. It's back to selling clothes again, at the time of writing. So, plus ça change?

When my mum moved into the house I grew up in, the rent, she says, was £9 a week. Built 23 years after Maison Bertaux opened, the place had latterly been a brothel. "People used to ring the bell," says mum, "and ask for Lady Lulu! When I told them there was no Lulu here, they would ask if they could come up and see me instead," (she was worryingly vague when pressed to confirm that she always declined such requests: "Aha!" she'd say with a wink).

Beric, left, with best friend William, right

When I was growing up, the more frequent unexpected visitors were people camping out on our front step, hoping to see some celebrity or other emerging from one of the studios across the street. Mum used to take them mugs of hot chocolate to keep them warm. Next door in a block of slightly lugubrious flats, with a cold stone stairwell that smelled of cabbages and incontinence, were some of the curious ladies mum liked to take under her wing. 'Auntie' Betty may have had a closer relationship with Johnnie Walker than with my family in any biological sense, but she was one of a few in whom a caring interest was shown, and whose gnomic, booze-scented pronouncements I would puzzle over if met in the street on my way home from school.

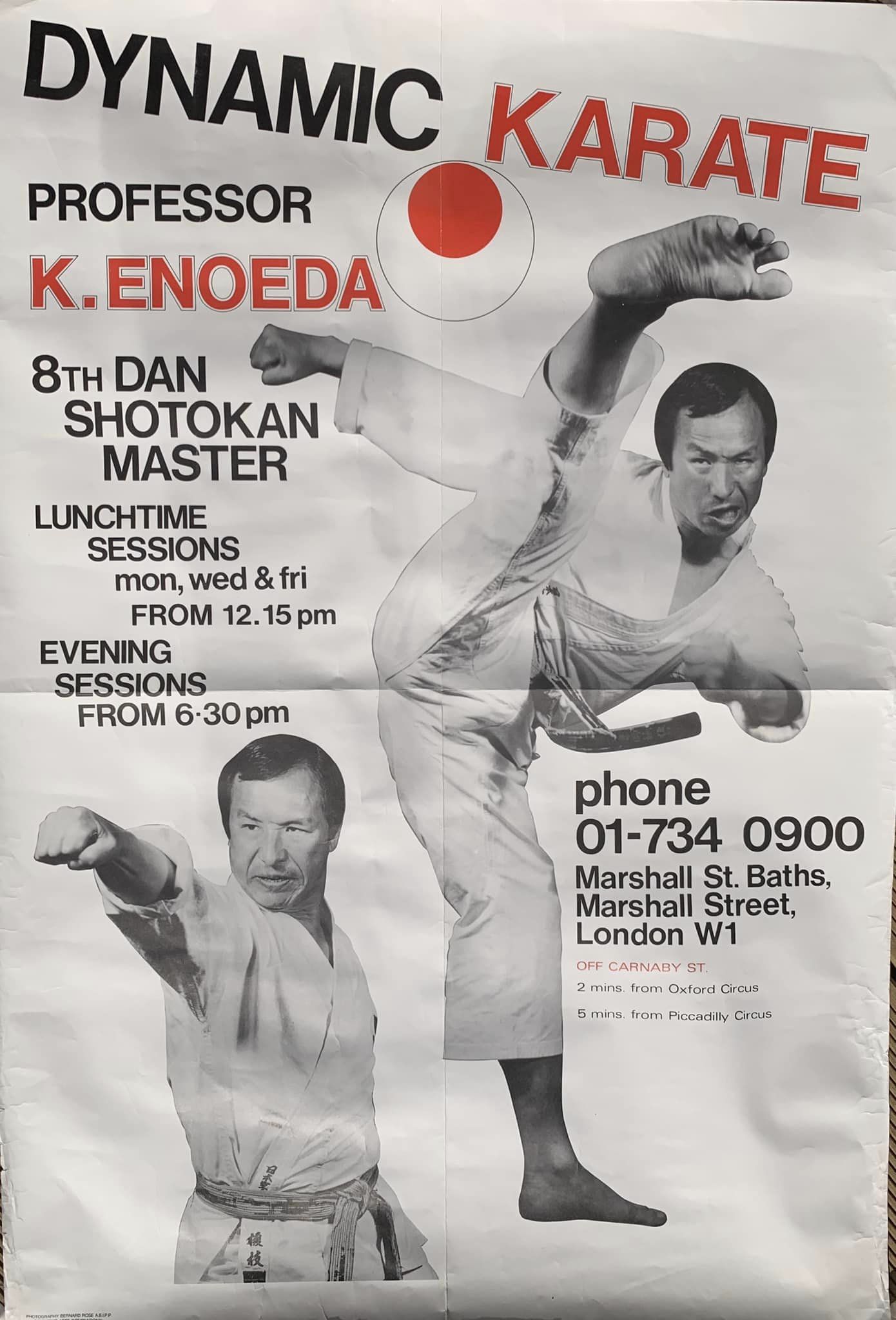

On the other side of our house was the leisure centre, where evening karate classes formed the soundtrack that rocked me off to sleep andtsuki'd into my dreams: "hi---YA!!" - followed by a series of synchronised thumps, as the students landed from their flying kicks. 'Dynamic Karate - Professor K. Enoeda' said the posters, with fearsome-looking pictures of the instructor. I learned later that he was incredibly well respected as a karateka, and that he'd had a rôle in Diamonds are Forever as a henchman of Blofeld's.

A few doors down was the newsagent where I earned my first pennies doing a paper round. The best bit of the job was getting access to a whole range of Soho buildings - the flats where Michael Toogood the vicar lived; the magazine publishers; the offices operated by the Police. Food, film, music, sex, clothes, souvenirs, booze, laundry, and more food (a lot more food).

As a boy the streets of London were not paved with gold, but with rubber. At least that was true of Carnaby Street, two roads down from our house. Orange, yellow, brown and white rubber tiles - installed, I read somewhere, in 1973 - gave a slight bounce to your stride (a gait I like to think I have never quite lost). As I grew up, the rubber paving became duller; odd things got stuck in it; cracks started appearing; it lost a good deal of its bounce and was eventually scrapped. Thus does a psychedelic pavement presage one's life.

Nowadays, it's a truism to remark that no one with a normal job can afford to rent a house in the centre of London; the council flats that were home to my alcoholic 'aunties' are rented privately to well-remunerated minimalists; the parking garage in whose unlocked cars I once drove on imaginary rallies has been turned into more of the dreaded 'luxury apartments', shielded by metal gates and enervated security guards from neighbours who are, in any case, far less kaleidoscopic than in my childhood.

The problem with money as an end rather than a means is that it is boring. Hands up who has their best bants with a banker? Money flattens and homogenizes, blends the painter's palette into a tasteful shade of taupe, and steamrollers it out towards the suburbs, from whose high-density homes we travel on longer and longer bus rides back to see the ever-more-mesmerising, yet ever-more-similar lights.

The Buddha has some very good stuff on facing up to change, on the absurdity of grasping at permanence and the misery that comes when we try. I frequently feel, reading the news, a sort of old git's dilemma: do I follow what's happening and get instantly depressed, or do I ignore it all and feel like a fraud? Pretending I'm in a science fiction film sometimes works - one with a more or less acutely apocalyptic ending. But all of it is a sort of fantasy, perhaps: a fantasy of the future; a fantasy of the past.

In defiance of my fantasy narrative of the present, I was delighted to meet, the other day, one of the people who now lives in my boyhood house. It seems to have been converted into a set of tiny bedsits. Stumbling out of the front door as I passed by was an apparition - early-30s? - of such beguiling and louche vagueness that it must surely have been drug-enhanced. Red hair in befuddled wisps and - was that a hospital gown he was wearing? "You're staring at my doorway." "Ah, sorry - it's just that I used to live here." "It's a shithole. Do you want to come in?"

Oh, Soho - you do keep coming through for me. This was no hegemonic hedge fund manager, no dissembling corporate shill, but old-school beautiful brokenness; a shard for the kaleidoscope; spangled and cracked, with a defiant residue of bounce. In short, just who I'd want to be living on the street where I grew up. It still smells like home.

I take the Buddha's advice. I focus on my breath. And the chocolate éclair.