City of the Sun

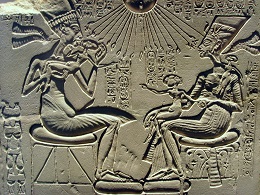

Aton Temple at Tell el-Armana - photo by Mark H. License: CC BY-SA 3.0

‘But the city he ran off to, now, that was a different matter. That was truly inspired. The site he chose was a barren bit of rock on the east bank of the Nile, as far from civilisation as you could possibly get. He called this site Akhet-Aton, which I know sounds insanely like his own new-found name, but for the first and only time in his life, my father was being poetic. It meant: “The Horizon of the Burning Face of the Sun”.’

Like many Ancient Egyptian words (or English words for that matter) the symbol Akhet can mean a variety of different things: birth-place, birth canal, flood, season of the inundation, cradle, seat, and horizon. And Merit was right, Pharaoh Akhen-aton’s choice of name for his new city was frankly poetic. Each morning when the sun rose behind the long, low-lying hills that bordered the city’s east-facing rear, it formed a living picture of the Akhet symbol.

Its construction was begun in Year 5 of Akhen-aton’s rule (circa 1346 BCE), marked by the carving of the fourteen boundary stelae dedicating the site to the sun-disk—the Aton—and though work progressed rapidly, it was in fact two years before the city became truly habitable. To hasten the completion of the project many of the structures were built from cheap, easily-made mud bricks; only the most important were clad in stone.

Akhen-aton, Nefretiti and their Children (Ägyptisches Museum Berlin) - photo by Gerbil License: CC BY-SA 3.0

Like any purpose-built new town these days, Akhet-Aton was designed as a model city. Based around the two dried-up river beds whose courses had flowed from the hills at the back down to the Nile, the long tract of land was divided into three natural sections. Dominating the central of these stood the royal palace, bisected by an extremely wide royal road running from north-to-south, parallel to the river. A bridge spanned the two halves, the so-called “Window of Appearances”, from which Akhen-aton and Nefretiti would throw precious trinkets to the faithful crowds below. The diplomatic records office (where Aashiq’s mother’s small plot of land is located in The Scarab Heart) is set at the back of the palace. Flanking both sit two Atonist temples, though the Great Temple to the north is roughly ten times the size of the more modest one to the south.

In the northern section of Akhet-Aton stood the northern palace, to which Nefretiti retires in my novel. This area originally contained high-quality housing (although all the houses were constructed to a similar blueprint), but later poorer families moved in, building smaller, more inferior dwellings as time progressed. The southern section of the city boasted yet another palace, possibly for the use of the princesses, and it’s here that many of the nobles had their estates.

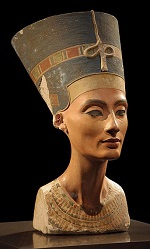

The Nefertiti bust, in Neues Museum, Berlin - photo by Philip Pikart License: CC BY-SA 3.0

One artist whose workshop was located in the southern suburbs was a man named Tutmose. You will be familiar with his one of his works—the bust of Nefretiti that now resides in the Neues Museum in Berlin. It’s an extraordinary piece, in that it appears to defy all conventions. It’s far too lifelike to fall into the traditional style of art with its rules of proportion and norms of expression that had barely changed for millennia. But it’s also too lifelike to be classed with the Amarnan style, which, under Akhen-aton’s guidance, broke tradition to experiment with a far more fluid approach, one depicting people with shockingly bulbous heads and swollen thighs. Compared to the rigid orthodox style it is a breath of fresh air.

But like the city itself, the Amarnan style was not to last. Although there is evidence of human habitation on the site at some point during Horemheb’s rule (which began approximately thirteen years after Akhen-aton’s death), it’s likely that the inhabitants were actually the wrecking crew, salvaging what building materials they could for use on future projects elsewhere.